Spoiler Warning: This review goes into plot details and specifics of the film. If you haven’t seen this film and want to, proceed with caution.

Will Sumrall: “He died with honor.”

Newton Knight: “No Will, he just died.”

Back in 2003, Gods and Generals, a three and a half hour Civil War epic, was released. This film told the story of the first half of the war mostly from the point of view of the South, particularly of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. In high school, my history class was forced to watch it. I’m not sure why, but I hope it was for the accuracy of historical events depicted rather than sympathy for the “Lost Cause.” That film was sympathetic to the Confederacy and portrayed its leaders as loyal, God-fearing Christian men who were fighting invaders who were infringing on their rights and freedoms. The fact that one of those freedoms was the right to own people, obviously infringing on their God-given rights, was barely touched upon during its relentless and self-righteous speechifying, rarely abandoning the perspective of its well-off commanders.

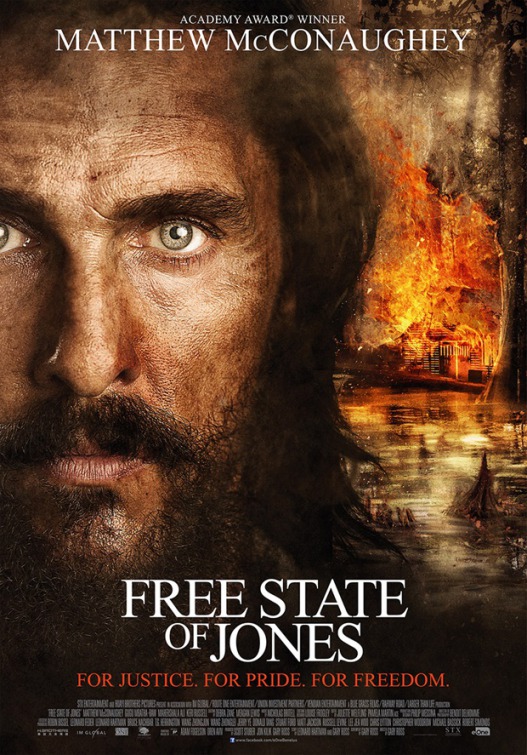

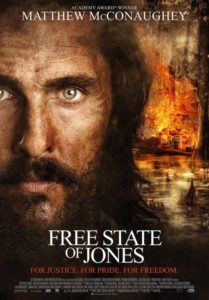

Free State of Jones, today’s entry in the Summer Blockbusters that Weren’t, instead offers the perspective of people too often neglected in tales of war: the poor and oppressed. This film tells the true story of Newton Knight (Matthew McConaughey), a poor farmer in Mississippi forced to serve as a battlefield nurse for the Confederacy. Seeing the senseless slaughter of his downtrodden neighbors while the wealthy that started this war are exempt thanks to laws protecting and rewarding those with enslaved people causes him to desert. When he makes it home, he finds Southern troops raiding everyone’s homes of food and supplies, leaving them with little to survive on. After helping one family fend them off, he escapes to a swamp occupied by runaway slaves led by Moses (Mahershala Ali), and befriends them. From this, Newton leads a revolt against the Confederacy and the idea that anyone has the right to keep others down to get rich. Meanwhile, he falls in love with Rachel (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), an enslaved woman who sneaks them supplies and eventually escapes.

The likes of Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee appear in nary a glimpse here, and General Sherman is only spoken of in correspondence, as the focus is on the people who were just trying to survive an unjust war. Free State of Jones doesn’t care about the men who commanded the army, but instead is about the truth of what they were fighting for. This film comes off as a response to the romantic notion of the Antebellum South, as well as the moral superiority of the Northern Union. In essence, Free State of Jones is about a rebellion within a rebellion, about a man who got tired of suffering for other people protecting themselves and saw slavery for what it truly is. This often neglected piece of history has a lot of potential to make a compelling story. It does, at times. It’s an ambitious film, with a lot to say, but lacks focus, with direction that favors long shots with little happening. Two contradictory statements probably sum this up: I like this movie, and it doesn’t really work.

In an interview with Slashfilm, director Gary Ross, of Pleasantville and The Hunger Games fame, made it clear that Free State of Jones was a passion project for him, stating that he worked on it for close to a decade. That passion can be seen on screen. This was billed as a Civil War movie, and it is, but it attempts to be more than that, being part biopic, part century spanning epic, part war movie, and part political treatise on the American Dream. Ross leaves as few stones unturned as possible, going through much of Knight’s life up through Reconstruction. However, so much ground is covered that the final film is a inconsistently paced and structural mess, more like a condensed mini series than a single movie.

The screenplay by Ross and Leonard Hartman treats the story as a saga by chronicling the struggles of one of Knight’s descendants, Davis, portrayed by Brian Lee Franklin. Ross shows how slow progress really is, breaking down the myth that the end of the war solved much at all. Newton ended up falling in love with Rachel, and they married. As a result, Davis was of one-eighth black descent, and his marriage to a white woman was considered illegal. Thematically, this parallel storyline compliments the main plot of poor citizens and black slaves being exploited, harassed, and killed. Almost a century doesn’t change much and it’s sobering how recent these events are. But rather than book-ending the film, these scenes are placed at random throughout, starting at the middle of the story. The transitions are jarring, and will likely confuse and distract.

For all of Ross’ passion for the material, his style is more intellectual than emotional. He takes his time in the first half, building up the anger and resentment of Newton and his cohorts, but it never feels like it truly boils over. The cinematography and editing style shifts periodically from long shots to quick edits, with little in the way of rhythm. Techniques such as quick cuts to show discomfort and shifting between angles during a scene to show shifting power dynamics are employed without those reasons to justify them. At times, the style undercuts the emotion. For example, during a scene where a few of the Rebels, who attempted to surrender, are found hanged, the film cuts from that moment during the day, to later at night in the swamp to show Newton crying. Why he couldn’t have been there to find the bodies, I have no idea. Numerous extended takes and close-ups reveal nothing. This may seem nitpicky, but it’s an example of simplicity and restraint can go a long way, and how a more focused script may have made this movie more interesting and exciting to a general audience.

As Newton Knight, McConaughey gives a powerful, passionate performance. He portrays him as a man equal parts angry and tired, increasingly disillusioned first with his home state, then the Confederacy, the Union itself, and finally the entire country. For a war film, few battles are shown, most of which are small scale skirmishes. A large amount of time is spent exploring the Reconstruction era, where it gets hammered home how little either side of the war actually thought about the people who suffered. The slave owners were forgiven and their wealth restored. The rights of freedmen went unacknowledged, with those who tried to rise above their station hunted down and killed. Votes went uncounted. During this period of so-called peace, the irony becomes clear: the war was the easy part.

This often brushed-off period of history makes you feel raw and painful at times during the film. Other times, it’s more of a classroom lesson. Due to the amount of history crammed into a 2 hour 20 minute film, years and events are glossed over with a mere text block explaining things. The result is that Free State of Jones resembles a PBS documentary.

Perhaps these intrusions were a device to track what Newton and his forces were doing in all likelihood. To expect complete historical accuracy here would be foolish. Historical sources telling the story of this rebellion are surprisingly difficult to come by, unbiased ones more so. The whole truth of who Knight really was and what happened during his fight may never be known (his actual birthdate isn’t even known). Ross needed to work with what had, and fill in the blanks elsewhere. The instigating event of his desertion is the Battle of Corinth, during which his nephew dies despite Newton’s best efforts to protect him. His nephew is played by Jacob Lofland, who has been in several things, but I mostly know him as young Pierce Brosnan in the fine Western series The Son. Why yes, my brother-in-law is in that show, why do you ask?

The fact that this didn’t actually happen isn’t necessarily a problem, though I wonder why Ross found it necessary to add. The obvious answer is to give Newton a more personal inciting incident to start his arc, but it comes off as incredibly calculated in a Hollywood way. Newton Knight was already against the war, both in history and movie, and his nephew’s death feels like a cheap way to justify an action that was already justified, especially because the character is forgotten pretty quickly.

Like the nephew, other characters feel like props for Newton’s journey, propping him up to look, as A.O. Scott said, “unambiguously heroic.” Ross attempts to avoid a white savior narrative, but he doesn’t entirely succeed. Part of this may have been unavoidable; due to the records that were kept and the story being told. The movie wisely avoids suggesting that Newton’s lot in life is as bad as the slaves he befriends, and it doesn’t shy away from how fruitless his actions seem, yet Rachel is written as an obligatory love interest who assists the main character in his arc. Mbatha-Raw does fine work, but she only gets a couple brief scenes to portray her motivation and pain. Moses gets more, such as a family and the motivation of registering freedmen to vote, and Ali is great as always, but when he is lynched, the camera focuses on Newton finding his body alone, never showing the body itself. McConaughey sells the hell out it, with no trace of vanity, but for all the emotion and horror, the fact remains that this tragedy is being shown through a white character’s eyes (It should be noted that Moses is fictional as well). To be fair, this criticism also applies to Newton’s first wife, played by Keri Russell, who shows up a few times to look helpless. It’s a thankless role, and the fact that she is always with their child makes Newton look like he abandoned them, however unintentionally. Her identity is confusing as well. Until Newton acknowledged the child as his towards the end, I was certain that Russell was playing his sister!

With Free State of Jones, Gary Ross set out to make a different kind of war film. This movie shows the result of the Civil War among the majority of our country’s Southern citizens. It’s a history that needs more exposure. This is a film about how much further our society has to go before true equality and justice are reached. Fittingly, this is also a movie that needed some time before it was ready to make that statement.

GRADE : C+

Free State of Jones has an admirable story and themes, but I can understand why theatrical audiences found it dull. Ross’ direction lets the material down, though there are enough bright spots and good performances to inspire some thought. It takes too long to get going, and once the movie’s true purpose becomes clear in the second half, it may be too late for many people to care. Nevertheless, the bright spots are compelling, and a Civil War film from the perspective of the downtrodden is a unique thing, and its condemnation of the War’s perpetrators is bold and cathartic. Hopefully, a more focused and stylish version of this type of story can be made in the future.